Choose one:

A. Life imitates art.

B. Art imitates life.

Humans learn from experience, and stories (art) are often drawn from our experiences. So one might think the answer is B.

But think about how young you were when people started telling you stories. Think about the books that were read to you by your parents. Think about the television programs and commercials you saw.

Most of those stories involved things you had not experienced yet -- journeys to far away lands, the experiences of children older than you, etc. Many of those stories involved things you would never experience -- talking bears, trips to the Moon, magical chocolate factories.

In ways big and small, those stories shaped your expectations of the experiences that would come later. You expected your "real world" experiences to match your "story book" experiences. Many times they did, and so you were comforted and well-prepared. Many times they didn't, and so you discarded the "story book" lessons and revised your expectations of the "real world."

And some times, when the "real world" didn't match your "story book" expectations, you discarded the "real world" and maintained your belief in the "story book." Or you re-imagined your experience with the "real world" so that it somehow matched or confirmed your "story book" expectations.

Some stories are so powerful they are hard to resist and hard to eradicate, even when they have outlived their usefulness. Those stories that are particularly powerful, especially for an entire culture or nation, can be called "myths." These are stories that have more power than fact. Their veracity is not nearly as important as their ability to influence and motivate groups of people. Because they are so powerful, it is important for us to understand them.

I know this most clearly from my experience teaching American literature and from my experience with American Indian Studies. The American Indian most commonly found in American literature has little or no relationship to any actual, living, breathing Indian. This started with Columbus and continued for hundreds of years. It still goes on.

Like someone pounding a square peg into a round hole, the Europeans who came to the Americas forced Indians to fit into the categories and expectations they already had in place. Many of the Europeans based their "real world" interactions with the Indians on their "story book" expectations. And American Indians paid the price for that. They still do.

But the power of narratives to influence behavior and belief can be seen in almost every aspect of human life. From politics to love to family relationships to international diplomacy. And politicians are no less susceptible to this influence than other people. In fact, many times they get elected based upon their ability to evoke narratives, regardless of their truth or usefulness.

The Florida legislators and Gov. Jeb Bush seemed to have had a "story book" in their heads when they passed their state's "Stand Your Ground" law in 2006. They seemed to understand their "real world" of 21st century life in Florida through the filter of a Wild West "story book." Theirs was a world where bad guys roam the streets, like Jack Palance in Shane, terrorizing decent, church-going folks. Theirs was a world where a man should have the right arm himself against such brazen attacks upon his person and property. In fact, theirs was a world imagined as being so threatening and dangerous that a man needed the right to bear arms no matter where he went; a man should be able to protect himself with deadly force regardless of where he was.

Richard Slotkin wrote a book about the power of such Wild West narratives in American culture, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. He states the frontier myth is a "vein of latent ideological power." It speaks very deeply to mainstream America's beliefs about itself, confirming its self-image as a nation of rugged individuals, heroes in an epic tale of people civilizing a savage wilderness. It is a myth cited often by politicians because it is a powerful tool for "explaining and justifying the use of political power."

Never mind that Florida was not part of the Wild West. Never mind that the "frontier" phase of American history ended more than 100 years ago. The Florida legislators were forcing the "real world" to match the narrative that was in their heads. By allowing private citizens to protect themselves with deadly force, they were holding back the forces of chaos (often times in the shape of ethnic minorities and immigrants).

They were not alone. Other states have similar laws. This notion of the frontier also shapes other issues in the nation. The illusion of radical independence and self-reliance shapes everything from debates about education to health care.

So on the night of Feb. 26 in Sanford, George Zimmerman probably had a story in his head, a story similar to that in the head of the legislators who passed the law that has kept the local police from arresting him. In that story, he was a good guy. In that story, young men with dark skin were likely to be bad guys. In that story, the bad guys didn't wear black hats, like Palance did; they wore hoodies. In that story, bad guys were willing to attack good guys and do them harm, so good guys were justified in shooting first. So long as they claimed it was in self-defense, their actions were legal.

We can only guess what story Trayvon Martin had in his head.

I believe in karma. I don't mean the kind of karma that involves reincarnation. I mean its more basic definition of "cause and effect." I believe that generally we experience the consequences of our actions, and generally they are in line with each other. I often times say, "You have to own your karma." By that I mean you must accept the consequences of your actions. I am not saying Trayvon Martin somehow brought this upon himself. Karma does not eliminate tragedy or injustice. But his death is part of the karma the state legislature must own. When you make it easier for people to legally carry handguns, and when you make it easier for people to legally shoot other people, this will almost guarantee that more innocent people will get killed.

State legislators who opposed the "Stand Your Ground" law said as much. When the bill was being debated, Sen. Arthenia Joyner said, "When you give a person the right to use deadly force anywhere they’re lawfully supposed to be, then we open Pandora’s Box, and inside the box will be death for some persons."

Although I am an "English teacher," I prefer to describe myself as a Story Teacher. More than talking about grammar and writing, I spend more time talking about stories -- how we tell them, why we tell them, how we change them, and how they change us.

Stories are powerful. They can have serious consequences. Ask George Zimmerman. Ask Trayvon Martin's family.

Friday, March 23, 2012

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

The Big Bitch Theory

Kurt Vonnegut was known as a fiction writer. It seems he may have been a bit of a prophet.

Kurt Vonnegut was known as a fiction writer. It seems he may have been a bit of a prophet.In one of his futuristic short stories, he described a United States where barriers against foul language in public had been dropped: "This was a period of great permissiveness in matters of language, so even the President was saying shit and fuck and so on, without anybody’s feeling threatened or taking offense. It was perfectly OK."

I know things haven't gotten that bad, but I have noticed the pervasiveness of the word "bitch" lately. It seems every few years a new word breaks the language barrier for television and public discourse. Before "bitch" the hot word was "douche." That went from a word not even used in commercials for one to a cheap laugh on sitcoms, from How I Met Your Mother to Cougartown. (A blogger noted the douche-phenomenon in 2010.)

I am no prude when it comes to language. I learned to curse in a news room, after all. But there is a time and a place for everything, and it seems that "bitch" has become the curse du jour -- it is everywhere these days. There is Bitch wine and Skinny Bitch cookbooks. Internet memes of "Bitch please" (yes, usually missing the appropriate punctuation) have become passe -- even those depicting the epitome of wholesomeness, Charlie Brown and Snoopy.

Perhaps an early sign of the word's impending invasion was in 2007. That is when a character as unvulgar and untimidating as Sheldon on The Big Bang Theory used the word. In an episode titled "The Big Bran Hypothesis" he says, "Ah, gravity. Thou art a heartless bitch."

The word has even made its way into the names of two TV series: GCB (Good Christian Bitches) and Don't Trust the B---- in Apartment 23.

I should say "bitch" is implied in both titles, but I have heard that the original titles spelled the word out. Oddly enough, both shows are on ABC. I always thought that B stood for Broadcasting. I guess not.

But the word is used in ways other than to refer to bad-tempered women. For instance, Wolowitz and Raj, again from The Big Bang Theory, have both referred to their male friends this way. In "The Hofstadter Isotope" Raj says, "Let's roll, bitches." In "The Luminous Fish Effect" Wolowitz says, "What up, science bitches?"

The comedy results from the disjunction between their personas as nerdy guys from Cal Tech and the "street" use of "bitches." Raj is probably saying it ironically, knowing it sounds funny, but Wolowitz, in this instance, is trying act tough and cool to his friends in order to impress a woman. The use of "bitches" here implies he is the leader of the gang and they are his subordinates.

Even when bitches refers to men, it still carries its misogynistic meanings. In the distant past, the word had meant only a "bad-tempered woman." However, thanks to rap lyrics (and prison jargon), it now carries a host of other meanings -- all pejorative and all misogynistic.

In an academic study titled "Misogyny in Rap Music," the authors, Ronald Weitzer and Charis Kubrin, state the masculinity espoused by popular media representations of men "glorify men's use of physical force, a daring demeanor, virility, and emotional distance." Rap lyrics exaggerate those tendencies into caricatures, but those caricatures can have powerful influences on audiences.

We can see why the writers of The Big Bang Theory would make comedy of their man-child characters taking hypermasculine poses.

This masculine ideal conveyed in rap lyrics many times depends upon the domination, exploitation, and degradation of women -- and of other men, who, since they can be dominated, are associated with women. That is to say, the word perpetuates the destructive idea that female = bad. Women are sex objects. Women are weak. Women are inferior. Dominating women (and men who are like them) is socially acceptable.

So, when "bitch" gains such widespread -- even laughing -- acceptance, I get worried that its misogynistic implications also are gaining that acceptance. Some people might argue that frequently using the word robs it of its power and somehow weakens the values it conveys. But I am not convinced this is true.

I hate to produce a grand narrative that sound like conspiracy theories, but the wide acceptance of "bitch" could be part of the larger cultural battles being waged elsewhere -- in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, in the controversy surrounding Rush Limbaugh's comments about Sandra Fluke, in the debates on contraception being covered by health insurance plans, and in the various efforts by state legislatures to dictate how women can interact with their doctors.

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Tonto Shops at J. Crow

|

| Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer |

The image and the discussions surrounding it raise the issue of authenticity.

Depp's headpiece has gathered the most attention. (For the moment, I will set aside the issue of casting Depp as an American Indian.) Some friends were pointing out that the headpiece seems inspired by a painting (I am Crow by Kirby Sattler). This accessorized bird raises the question of why would Tonto be wearing a headpiece from the Crow? Tonto was apparently Apache or Potowatomi (I have seen different references from histories of The Lone Ranger series). After the 1830s the Potowatomi would have lived primarily in Kansas and Nebraska, having ceded their lands in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois. At the same time, the Apache lived pretty much where they always had: New Mexico, Arizona, West Texas, and Northern Mexico. At that time, the Crow were living in Montana and Wyoming.

So some might ask how Tonto would have come upon such a headpiece. Perhaps he saw it in a J. Crow catalog.

|

| Texas Rangers |

No one ever wonders about the Lone Ranger's mask -- is that really going to keep anyone from recognizing him? We understand the mask to be functioning as the sign of "disguise" and we do not question its ability to truly hide an identity.

No one asks about the historical accuracy of a Texas Ranger being friends with an American Indian. One of the main reasons for the creation of the Texas Rangers was to kill Indians. The Comanches on the western edge of Texas were giving the Texans fits, and so the Rangers were sent out to deal with them.

The Lone Ranger is a historical fantasy, not history. A historical fantasy tries to rewrite the past to make it more consistent with the present. People re-imagine their past to reinforce their beliefs about themselves today. America wants to think of itself as racially tolerant, as completely comfortable in its multicultural self, so it imagines a Texas Ranger and an American Indian being great friends to help it forget the ugly facts of frontier history.

|

| Clayton Moore & Jay Silverheels |

Is it silly to ask for authenticity in depictions of Tonto? The character of Tonto never had any authenticity. Like many American Indians in American film and literature, he was the figment of white America's imagination.

I do not want dismiss the real-world implications of such stereotypical depictions. I wrote about this in "Symbolic Indians vs. Smiling Indians." But the whole Lone Ranger franchise is a kind of drag show, so perhaps no one should take it too seriously. Perhaps we should lean back and laugh at its latest version, even laughing at the parts it may be trying to get right. Or at least wait until the movie is released and see how it all plays out.

Thursday, March 1, 2012

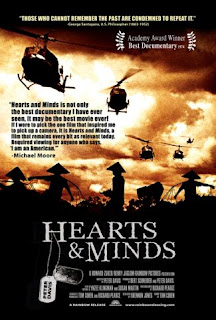

We need to win the hearts and minds... of Americans

|

| Brad Graverson/Torrance Daily Breeze |

When the United States military was in South Vietnam, there was much talk of “winning the hearts and minds” of the people there. Not that it did a very good job of that.

The phrase “Hearts and Minds” was used a good deal by President Johnson in reference to the war in Vietnam. He said at one point, "So we must be ready to fight in Viet-Nam, but the ultimate victory will depend upon the hearts and the minds of the people who actually live out there. By helping to bring them hope and electricity you are also striking a very important blow for the cause of freedom throughout the world."

The idea was that efforts to defeat the enemy’s army were pointless if the America could not make allies of the people for whom it ostensibly fought.

The phrase also became the title of a 1974 documentary that described the failure of the United States to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people.

It is a phrase that has been repeated often in relation to the U.S. military missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. And as the recent Koran-burning incident in Afghanistan proved, many of the hearts and minds there have not been won.

Last week I heard a report on the radio that made me think of the various efforts the United States has made to “win the hearts and minds” of the people in countries the U.S. military has occupied. It made me think, “If only America tried to win the hearts and minds of Americans.”

Last week the Los Angeles City Council voted to change its enforcement of school truancy. The program was originally intended to curb daytime crimes by teenagers, but in time it had become something else. Police officers were arresting students just outside of their schools – students who were headed TO school, not sneaking away from it.

Police officers were waiting at city bus stops near the schools, arresting students as they stepped off the bus. Since they were not in the company of their parents and since school had started, they were deemed truant. They were arrested and given heavy fines.

I am not a police detective, but I would wager that not many crimes are committed by teens as they run from the bus to their school’s front doors.

Between 2005 and 2009, police issued more than 47,000 citations for the daytime curfew violations (truancy). School police issued 11,000 of those citations – that means, they were issued on or near school grounds -- and not one of them was issued to a white student.

Hearts and minds.

It seems that poor students and students from single-parent homes are more reliant upon public transportation than are middle-class students or students from two-parent homes. The poor kids were at the mercy of the city buses to run on time; if the buses ran late, then the students were liable to be arrested on their way to school. The kids who had a parent to take them to school might be late, but since they were not alone, they were not “guilty” of violating the curfew laws. So you could have a situation where a poor student was in the process of being arrested while an equally late student was allowed to pass because his mother was dropping him off at the school’s entrance.

Hearts and minds.

In some cases, when students realized they were going to be late to school, they decided to go back home. It was better to miss school altogether than to risk getting arrested – and to risk having financially strapped parents pay a fine that could reach $800.

Is it any wonder that young people, especially young minority students, can grow to resent the police? Is it any wonder that young people, especially young minority students, can feel disenfranchised, alienated from the government that supposedly represents them?

Some politicians like to talk about the United States as a welfare state that encourages dependency by the poor upon the services of the government. But programs such as this truancy enforcement look more like harassment than help.

Similar disparity of enforcement can be found in drug-related arrests. Studies indicate that illegal drug use among minority teens is no higher than illegal drug use among white teens, yet minority teens are FAR more likely to be arrested for drug possession. And those arrests (and convictions) often create large roadblocks for those young people to escape the cycles of poverty that plague their neighborhoods.

Government and police strategies designed to be “tough on crime” or "make the streets safe" can easily be seen as being programs designed to keep certain segments of America poor and powerless.

Government and police strategies designed to be “tough on crime” or "make the streets safe" can easily be seen as being programs designed to keep certain segments of America poor and powerless.

Fortunately, the Los Angeles City Council voted to end its counterproductive truancy policies, to stop arresting students so frequently and fining their families so mindlessly. It has voted to change its policies to more accurately reflect the goal of truancy laws: keeping kids in school.

It is a small step toward winning the hearts and minds of America’s at-risk youth (who ironically are sometimes put at risk by government policies) and their families. It is one step toward convincing them the nation needs their success and the nation is dedicated to helping them achieve that success. Many more steps remain.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)