|

| Capt. Jack Sparrow, the world's favorite underdog |

In this sense, the nation may not be much different from people who typically look to their past, especially their childhood, to understand what most shaped their adult personalities. Sometimes they do this and ignore their more recent influences.

But underdogs need top dogs, and whom people choose as their top dog, as their bully, as their oppressive force, can possibly tell us something about the audience's values.

|

| Lord Cutler Beckett |

Toward the end of the third film, Cutler Beckett is killed. As his flagship is destroyed, he falls into the water. A ghostly shot captures him sinking into the ocean enveloped in the flag of the East India Tea Co. The image suggests that he has been brought down by his own plans, his own overreaching and conniving. The image also suggests that the power of the evil corporation has been destroyed, at least temporarily.

I thought it was interesting that he sinks in a corporate flag and not a national flag. That makes sense in that Captain Jack Sparrow is not an American, and the film is set in a time before the American Revolution. It also makes sense in that the film is intended for a global audience, and everyone around the world does not identify with the British as potential antagonists. Great Britain is the stern father figure in America's rebellious childhood. The rest of the world, not so much.

However, interpreting this choice of top dog from an American perspective, we can see it fits with a larger pattern. Frequently the bad guy/top dog in popular films have been signifiers of corporate excess.

In Aliens, for instance, the company is more concerned about the financial possibilities of the chest-splitting monster than it is about the safety of its employees.

In Avatar, it is a corporation and not a nation that seeks to destroy the Na'vi's Hometree in order to reach the mineral deposits beneath it.

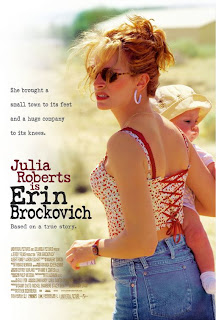

Similarly, to name just a few films, corporations are the bad guys in Norma Rae, Silkwood, Erin Brockovich, The Insider, and Michael Clayton.

I like to look at the stories we tell as similar to dreams. Like dreams, stories can provide clues to our deepest desires and fears. But whereas dreams can provide insight into an individual, popular stories can provide insight into the society that enjoys them, into what we could call a collective unconscious. This is especially true when we find many stories fitting into particular patterns.

Arthur Asa Berger says something similar to this in his book Signs in Contemporary Culture: An Introduction to Semiotics: "Dreams, Freud tells us, are functional: they have a meaning and they do something for the dreamer. In the same light, our collective dreams (or is it daydreams) have a meaning and provide people with a number of gratifications" (96).

In the case of films about corporate bad guys, we could say the "gratification" we get from them is an expression of our anxiety about corporate influence in our lives. But I find it puzzling that this anxiety gets little expression in our real lives. That is, as a society we seem to enjoy films about corporate bad guys, yet we have a political system that seems to cater to corporations.

Someone might say this is a case of the American people accepting fantasies over reality. Instead of acting effectively upon the anxieties depicted in the films, audiences have their anxieties alleviated in the dark and leave the political system unchanged.

However, other Hollywood bad guys represent real-world anxieties, and these other anxieties do find expression in real-world actions. At election time, not much traction is gained by discussing the need to counter corporate greed or exploitation. Yet much traction is found in discussing the threat of foreign nations or causes; Nazis, Russians, Japanese, and Islamic terrorists have all taken their turns as Hollywood bad guys. Electoral points are scored by talking about the threat of crime; many, many Hollywood bad guys are criminals of the more common type, and often times they are represented by ethnic minorities (in that way they are twofer bad guys -- two anxieties in one villain).

Arthur Asa Berger says something similar to this in his book Signs in Contemporary Culture: An Introduction to Semiotics: "Dreams, Freud tells us, are functional: they have a meaning and they do something for the dreamer. In the same light, our collective dreams (or is it daydreams) have a meaning and provide people with a number of gratifications" (96).

|

| Sally Field in Norma Rae |

Someone might say this is a case of the American people accepting fantasies over reality. Instead of acting effectively upon the anxieties depicted in the films, audiences have their anxieties alleviated in the dark and leave the political system unchanged.

However, other Hollywood bad guys represent real-world anxieties, and these other anxieties do find expression in real-world actions. At election time, not much traction is gained by discussing the need to counter corporate greed or exploitation. Yet much traction is found in discussing the threat of foreign nations or causes; Nazis, Russians, Japanese, and Islamic terrorists have all taken their turns as Hollywood bad guys. Electoral points are scored by talking about the threat of crime; many, many Hollywood bad guys are criminals of the more common type, and often times they are represented by ethnic minorities (in that way they are twofer bad guys -- two anxieties in one villain).

I have no explanation for this particular disconnect between the stories we enjoy and the world we live in. I will keep looking.

Note: This was originally published with the title "Arg. America Be a Confusing Nation."

Yes, we love to hate on corporations. But most people forget that even the middle class are very dependent on them for retirement income. Let's sock it to the big corporations. - Whoa, not so fast. My IRAs are expecting them to prosper if I'm expecting to retire with dignity.

ReplyDeleteIt is sometimes troubling to me that we treat the corporation as a distinct person. It is however, a person without a soul, and with one primary reason for being- to make a profit. A real person is much more complex than that.

Currently, my favorite thing to question the corporations on is in the arena of copyright and intellectual property. Originally, copyright law was written to ensure that a person could expect to earn a fair income from a creative work, while at the same time enable the spread of and sharing of ideas. We've come a long way from that. Nowadays, copyright seems to ensure that a corporation can earn enormous profits from creative works for indefinite periods of time. Mickey Mouse about to enter the public domain? Let's just lobby to change the law so that won't happen.

But we live in a time where these laws no longer make sense. The cost of reproduction and distribution of creative works is virtually nothing. We certainly need to be sure that the creator can make a living by being creative, but at the same time ensure that our culture is not held hostage to corporate profits.