Twitter can be a scary pool to dip your toes into.

If you comment about a popular topic, use a trending hashtag, or tag someone famous, your tweet can get attention you may not have wanted.

For instance, earlier this year I made a snarky comment about the array of bad haircuts Jon Bernthal has sported in his various film and TV roles. I did not tag him, but he saw and liked the tweet. Soon that tweet had more than 15,000 impressions. (I commented on the tweet to make it clear I thought he was a fine actor.)

No one attacked me (or my own haircuts), but the number of impressions made me nervous. I was uncomfortable getting that much attention, especially for a comment that might be considered mean.

Even when there is no risk of generating bad karma, a bunch of impressions can scare me. In August 2021, when The Chair was popular on Netflix, I tweeted a pitch for a show about adjunct faculty members. It received more than 46,000 impressions and more than 400 likes.

These thoughts came to mind recently after I saw an episode of Rutherford Falls from its second season on Peacock (NBC's streaming service). In the season's second episode, Feather Day (Kaniehtiio Horn) walks into the office of tribal casino executive Terry Thomas (Michael Greyeyes) and speaks in Mohawk. Her comment is not translated on the screen, and the closed captioning states "speaking Mohawk." She and Terry then have a discussion in English, and she exits the meeting with another untranslated Mohawk comment.

This prompted me to ask on Twitter about the lack of translation.

Not long after that, showrunner Sierra Teller Ornelas replied.

This is where the "fog of Twitter" comes in. Ornelas does not know me. We were not having a conversation about this episode. She had little context in which to "hear" my tweet. Was she hearing a complaint? Was she hearing snark? Her reply seemed a little defensive to me, calling back to a 50-year-old film to explain the lack of translation. Perhaps defensive is not the right word. Resentful? Irritated? I do not know her. This was not part of a conversation we were having. I had little context in which to "hear" her reply.

Perhaps she had second thoughts about her response, because a few moments later she added another reply:

As the "likes" for her response surpassed the "likes" on my original post, I wondered if I was getting dunked on. Did the people who liked her response think I was a dunderhead?

As I say, she does not know me. She does not know that I teach American Indian literature and American Indian Studies. She does not know that I talk about Rutherford Falls in class as an example of Native self-representation, as an example of visual sovereignty.

My Twitter profile mentions my teaching and my citizenship in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, so perhaps Ornelas checked that out and decided my question was legit.

I understand the impulse to not translate the Mohawk language. This decision might be related to a concept I discuss with my students: ethnographic refusal.

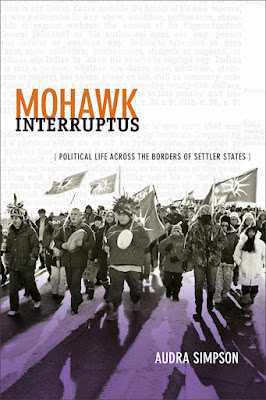

This describes the refusal of a Native person to explain their experiences, beliefs or cultural practice to an outsider, such as an anthropologist. This refusal makes sense in light of how knowledge of Native people has been misused and misinterpreted by the dominant cultures of the United States and Canada. Audra Simpson discusses this concept in her book titled Mohawk Interruptus.

I have heard the term also applied to creative decisions by writers, artists, and filmmakers. They have a story to tell, and they know non-Native people will be in their audience, but they refuse to have characters or narrators explain everything for them. Since so many members of nearly any audience are non-Native, great pressure can be applied to Native creators to explain everything. Native creators may resist that pressure because having a character explain the significance of a symbol, statement, ritual, or belief does not feel right aesthetically. They also might resist because explaining would reveal to outsiders some important cultural element that a Native community would prefer be concealed.

When discussing this element in my classes, I talk about the "anthropological curiosity" or "anthropological voyeurism" that some non-Native audience members bring to a book or movie. Some people in the audience are more invested in learning the cultural secrets of American Indian communities than how the central conflict is resolved or whether the characters are well drawn. This kind of curiosity can be tiresome for the Native creator who is most interested in telling a good story.

From what Feather and Terry say in English just after she enters, I assume her Mohawk statement was some kind of dig at his fancy office. That does not seem like sensitive cultural information or insider knowledge. Other things in the show are not explained, such as the inside joke of characters saying "Skoden" and "Stoodis." These words are rez-speak for "Let's go then" and "Let's do this" -- especially as challenges to a fight. These are titles for two episodes of the first season, and characters say these things to each other, but no one explains what the words mean. If you know, you know.

However, the decision to not translate Feather's Mohawk dialog because "It's not there to be explained" seems odd for a show like Rutherford Falls, because it spends a lot of time explaining things to its audience. In fact, I think one way the show is valuable to the general audience is how much it explains. One of its central characters, Nathan Rutherford (Ed Helms), seems to be a stand-in for the non-Native audience members. His function is to learn from his Native friends and alter his behavior and beliefs according to what he learns.

An example of the show explaining things for the benefit of its audience occurs in the second-season episode titled "Land Back," when Nelson (Dallas Goldtooth) tells Reagan Wells (Jana Schmeiding) that the artifacts in the tribe's museum collection want to be handled and visited with rather than be stored away or handled only with gloves. He tells her, "They've been kept away for far too long. Each of these items has an energy. They want to breathe. They want to be held. This doll wants us to visit with them." During his remarks, she looks at him skeptically, but this is a concept Reagan should be familiar with. She has a master's degree in Museum Studies, and she is dedicated to decolonizing the curation and presentation of her tribal heritage. She would know what he is doing when she sees him talking to the items in the collection. However, many people in the audience probably are not familiar with that idea. He explains it to her for their benefit.

Part of the cultural work performed by Rutherford Falls is explaining contemporary Native life to a non-Native audience. When I use the phrase "cultural work," I am thinking of Jane Tompkins' book Sensational Designs, in which she discusses the ways literature can "redefine the social order." Television shows can be very effective at doing this, changing the way audiences think about people different from themselves. In this case, redefining how non-Native people think of American Indians. Shows like Rutherford Falls and Reservation Dogs, by placing so much of their production in the hands of Native directors, producers, writers, and actors, can alter the stereotypical impressions so many Americans have of Native people.

Too many Americans think of Native people as living in the past. They identify American Indians with signs of the 18th century, with tipis and headdresses, etc. Even when they know that Native people live contemporary lives, the role they expect for Native people in popular culture is the Noble Warrior or the Bloodthirsty Savage, etc. These two shows do the important work of representing Native people living thoroughly contemporary lives.

I thought not translating Feather's Mohawk comments was interesting because Hollywood has often treated Native languages as interchangeable or, worse, not worth translating. A famous example is John Ford's The Searchers. The American Indian characters in that film are supposed to be Comanches, but many of the actors were Navajo. They spoke their language, but the film pretended it was Comanche they were speaking. The non-Native audience would not know the difference, and it did not matter what the actors actually said, since the captions would state whatever Ford wanted them to.

Such events are depicted in Reel Injun, a documentary about Hollywood's representations of Native people. That film presents a clip from a Hollywood Western, A Distant Trumpet (1964), with accurate captions instead of the originals. The Native actors are insulting the white characters, calling them snakes who crawl through their own shit, but this is not what the film's captions state. The film crew had no idea what the Native actors were saying. They probably did not care. You can watch the scene here.

The worst example is when a film states simply [speaking in foreign language]. Languages are not foreign to everyone. They are not foreign to their speakers. Refusing to translate the dialog seems dismissive. "What these characters are saying does not matter."

I think all languages should be translated and captioned for film and television. Characters make statements for reasons, and their dialog communicates motivations and intentions -- even if no other characters on the screen can understand what is said.

Hollywood has a history of dismissing Native languages, and so I like to see them translated on the screen. I think translating and captioning Native languages acknowledges them as carriers of meaning, treats them as equal to other languages. I know Rutherford Falls means no disrespect to the Mohawk language by not translating it; this is just my personal preference.

Finally, one contribution to the Twitter conversation made an excellent point about captioning and translating Native languages. If someone is a Mohawk language speaker but is also hearing impaired, they would appreciate the captioning service, even if the dialog is untranslated. Excellent point!

No comments:

Post a Comment